Bleeding Blue: The Dodgers and a Test of Conscience

By Nick Valencia | October 5, 2025

ATLANTA— For us, being Dodgers fans has always been about more than baseball. It’s an inheritance that carries both pride and pain.

My grandfather, Fernando Plana, was among the roughly 1,800 families displaced by the construction of Chavez Ravine. He lived there before the bulldozers came, and like so many others who had immigrated from Mexico, he was forced to start over somewhere else, again. He and my grandmother settled in Highland Park, and that’s where they stayed for the rest of his life.

I can still picture him: pressed sharp khakis, crisp white T-shirt, and that blue LA Dodgers cap resting perfectly on his tuft of hair. Despite what had been taken from him by the team and its owners, he died a loyal Dodgers fan.

In some way, that loyalty became a form of resistance—a choice to keep loving something that didn’t always love him back. Decades later, I find myself wrestling with that same contradiction.

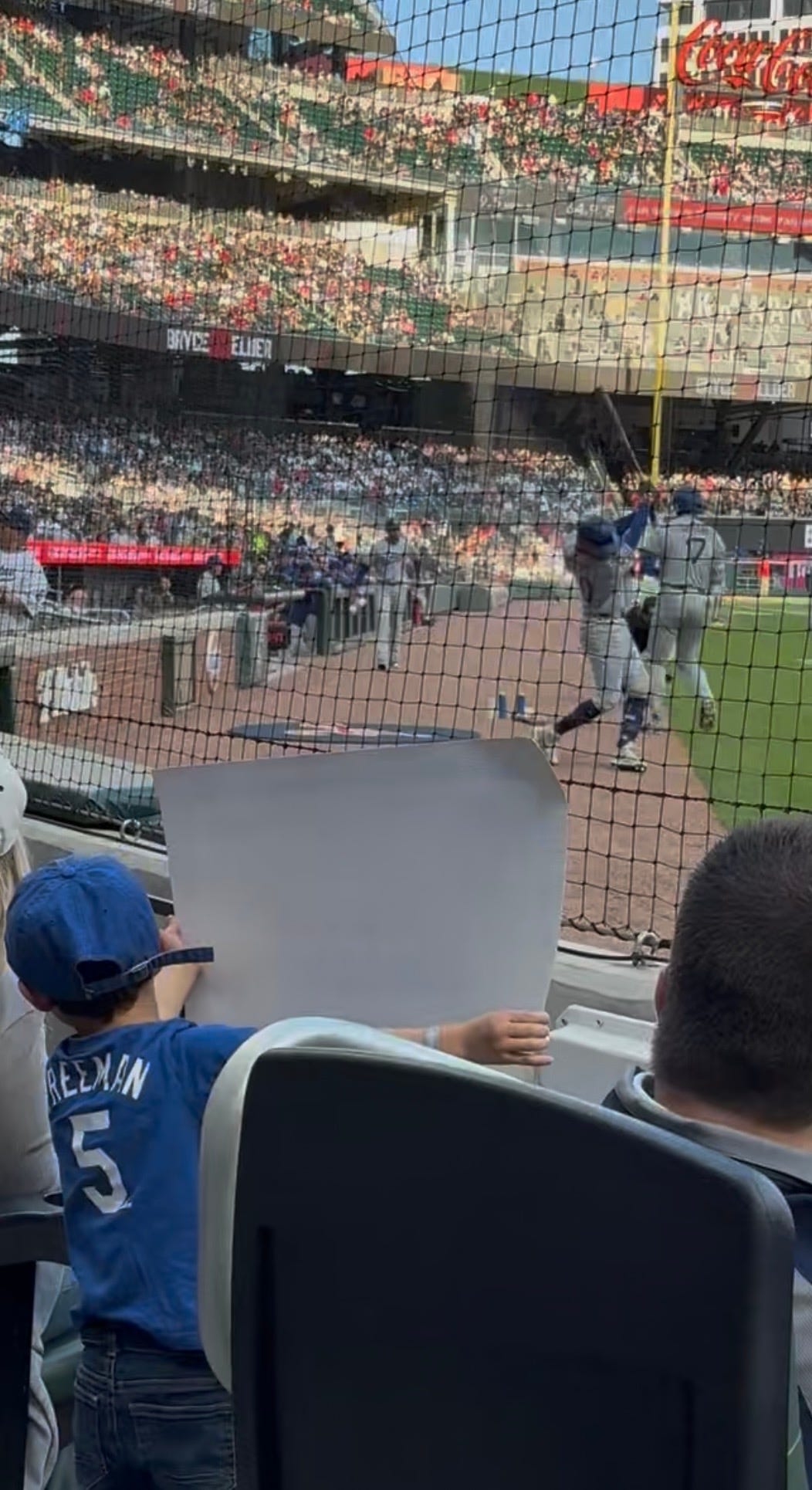

Living in the South, far from Los Angeles, I’ve held onto the Dodgers as a way to help my kids connect with their Latino roots—to feel the same pride I did growing up in Northeast LA surrounded by Chicano families who bled blue and rooted para “Los Doyers.”

That pride is harder to hold right now because the people who own my team are the same ones profiting off ICE detentions. The Dodgers front office is inextricably linked with the very system my journalism is fighting to expose.

It’s impossible for me not to connect the dots: the roar of the crowd, the hot dog sales, the billion-dollar stadium experience—all built atop the pain of people like my grandfather, and now sustained by those making money from the suffering of immigrants being detained, transferred, and dehumanized. And yet, I still go to games, watch them on TV, and update my kids in the morning on the highlights from the night before.

As Javier Cabral, editor of L.A. Taco, said recently, it’s hard for anyone outside of Los Angeles to understand what it means for a Mexican-American kid to love the Dodgers. He’s right. For us, it’s never been just a game. It’s identity. It’s survival.

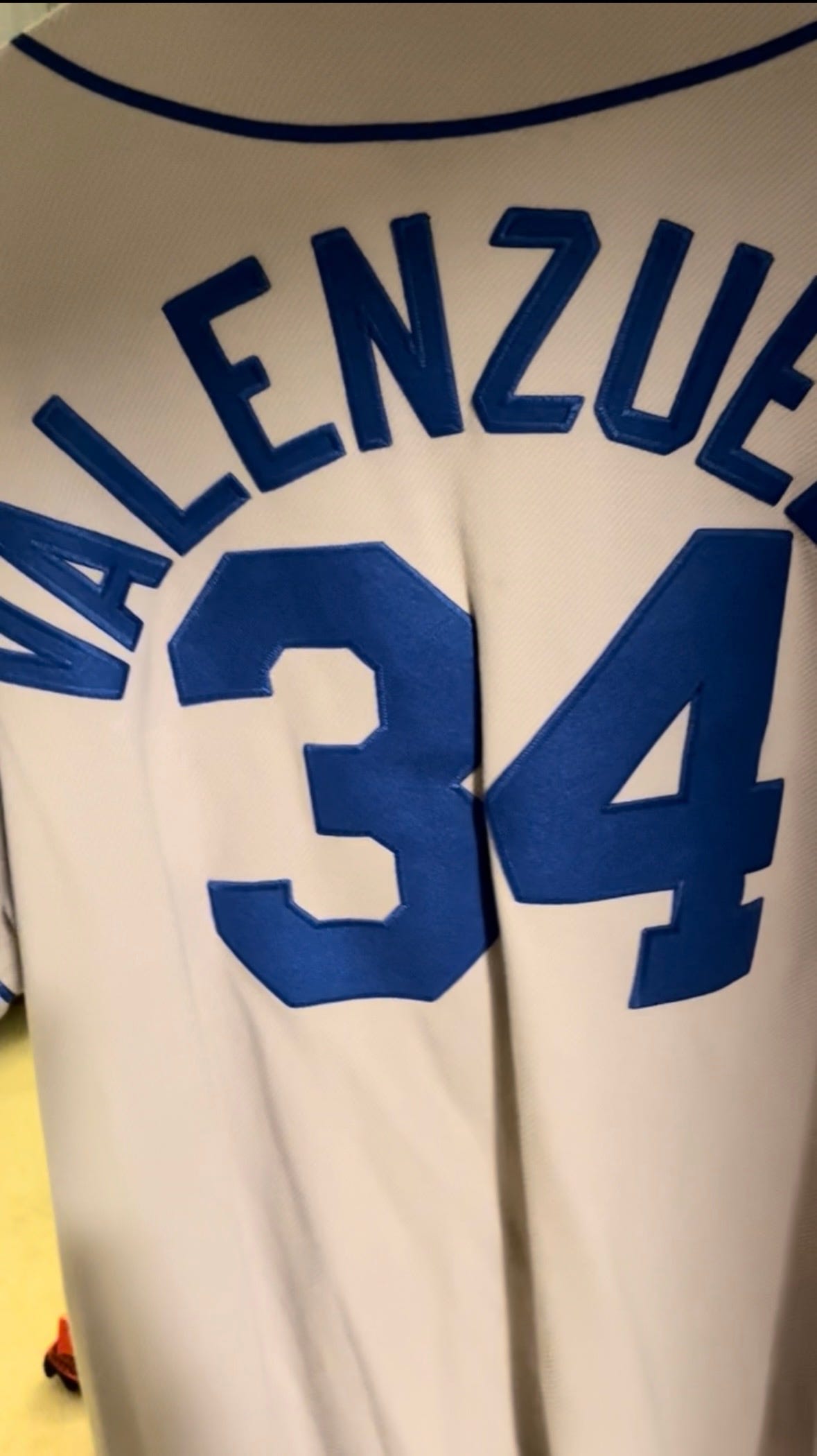

I think about Fernando Valenzuela, about Fernandomanía, about how he made us feel seen for the first time—how he gave Mexican-Americans permission to take up space in baseball and in America. I think about my dad and sitting on his lap in the living room during the ’88 World Series. Those memories are stitched into who I am.

Now, as I pass that love on to my own children here in the South, I feel the conflict more than ever. The Dodgers have become a test of my conscience. Today, they are a reminder of how loyalty and pain can live side by side.

Like my grandfather, I haven’t turned my back on my team, even if the owners have turned theirs on us. Because being a Dodgers fan was never about them. It was about the people they displaced, the workers who built the city, the kids who saw themselves in Fernando Valenzuela.

Maybe that’s what it means to be Chicano — to love something fiercely while demanding it do better. To love the Dodgers and bleed blue, even when the wound still stings.

Thank you for your poignant words. So many Americans are simply pretending that pain isn't part of the American story.

We need new owners. Could the public buy the team, like the fans of Green Bay? This would be the ultimate symbolic win.