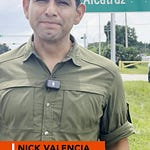

By Nick Valencia | October 20, 2025

ATLANTA— It’s easy to Monday-morning-quarterback a pandemic.

Hindsight is always 20/20, and nowhere is that truer than at the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What many Americans saw as flip-flopping—masks, surfaces, distancing—was, to scientists, the natural evolution of evidence.

But the gulf between those views proved disastrous, and we’re still living with the fallout.

Kathleen Ethier, who led the CDC’s Division of Adolescent Health during COVID, puts the lesson plainly: “We have to be better at communicating. We have to be better at communicating the importance of what we do. We have to be better at communicating about science and what the scientific process is and what you can trust and then what you can’t trust.”

She notes that early directions like wiping down surfaces were based on the best data available at the time—and changed as understanding improved. To scientists, that’s the whole point; to a public craving certainty, it felt like whiplash.

That distinction—between learning in public and looking unsure—eroded trust in real time. The story of COVID in the U.S. is not only a tale of a novel virus but of an old communications problem: truth delivered without translation. The agency failed to narrate its own learning curve. It didn’t show its math. To the critics, the CDC rarely said, “Here’s what we know, here’s what we don’t, and here’s when we’ll revisit this.”

The silence around uncertainty created space for others to speak with confident simplicity.

Into that vacuum stepped a new kind of public-health leadership. Health and Human Services is now led by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whose tenure has been defined by strong, sweeping pronouncements that often outrun evidence. The country has, in effect, traded uncertainty for unreliability—clarity of tone for confusion in substance.

Strong and wrong.

RFK Jr. was confirmed by the Senate on February 13, 2025, and sworn in the same day; the appointment reshaped federal public-health posture overnight.

The nations leading public health experts believe we are worse off today than we were at the height of the pandemic—not because viral threats have grown more complex, but because institutional trust has grown more fragile. Inside the CDC, that fragility is visible as fear and fatigue. This month alone, more than a 1,200 CDC employees received termination notices, with hurried reversals and partial reinstatements sowing deeper chaos. Unions and former officials describe a system in free fall, with vital functions—from Washington liaison work to library services and safety offices—gutted or whipsawed.

If you’ve followed our reporting, you’ve seen how these cuts ricochet through the agency’s mission. Lay off policy staff and you weaken Congress-facing briefings. Cripple the library and you slow the science that feeds guidance. Hollow out wellness and safety offices and you send a message to frontline scientists that their well-being is expendable. It’s not just operational harm; it’s symbolic harm—the kind that tells the country its referees no longer have whistles.

Ethier’s point is not an excuse for every early misstep. It’s a diagnosis for how to rebuild: narrate the process. Say the quiet parts aloud. When the evidence shifts, explain why and how it changed, not just what is now different. Be explicit about the uncertainty bands. Offer timelines for re-evaluation. And above all, resist the temptation to match misinformation’s confidence with counter-certainty. The antidote to “strong and wrong” is not “stronger and louder.” It’s “clearer and accountable.”

Science did not fail during COVID because it changed; it failed the public because it didn’t explain its changes. That is fixable. What’s harder to fix is a culture that now rewards certainty without proof.

The CDC’s biggest failure wasn’t getting it wrong—it was failing to explain why getting it wrong is often the first step to getting it right. The only way back is through transparency, humility, and the discipline to keep telling that story, especially when the answers are still coming into view.